The staggering cost of Montana’s flash drought

The 2017 flash drought that parched the entire state of Montana and most of South Dakota, severely impacted the profitability of ranchers and farmers. In western Montana, fires burned some of the largest acreages in recent history.

THE STAGGERING COST OF DROUGHT

The drought resulted in one of the biggest wildfire incident reports (over one-million acres) and caused virtually 100% crop loss in northeastern Montana. The U.S. Dept. of Agriculture estimated the crop loss to be in the hundreds of millions of dollars, and one question was on everybody’s mind—why did no one see it coming?

GETTING THE RIGHT DATA

The 2017 Montana Dept. of Natural Resources and Conservation spring drought report indicated plenty of water: “By the end of the month, almost all drought concern was removed from the state, with the exception of Wibaux and Fallon Counties….As of May 9, 2017, Montana was 98.45% drought free.” But in late May, an abrupt shift in weather conditions led to one of the hottest, driest summers on record.

The problem, says Kevin Hyde, Montana State Mesonet Coordinator, lies not only in the need for more weather data but in obtaining the right kind of data. He says, “One of the reasons drought was missed was because we’re still thinking you measure drought by snowpack and how much water is in the river, which is really great if you’ve got water rights. But we’ve got a lot of dryland out there.”

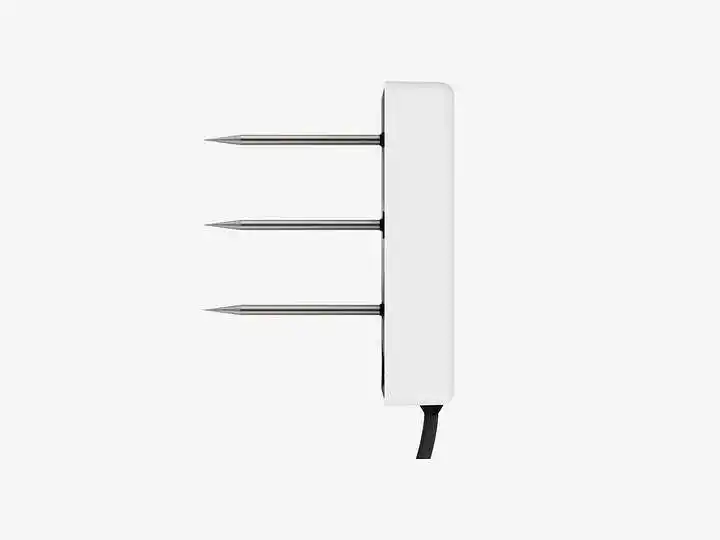

SOIL MOISTURE ILLUMINATES THE BIGGER PICTURE

Heavy rains came mid-September of 2017, which led some people to believe the drought was over. However, changes in soil moisture told a different story. Very little of the rain made it into the soil. “At the Havre, MT station you can see we had some heavy precipitation events. Then we had early October snows. So people expected good soil water recharge. But at the end of the day, we didn’t get it. On Sept.15th, soil moisture sensors showed a big soil moisture response at the surface but only a marginal response at 8 inches.” The melt of early October snows onto the soil, still damp from the September rain, drained to 20 inches or more. But as the snowmelt dissipated, there was minimal net gain going into the winter.

PREDICTIVE MODELS NEED MORE COVERAGE TO BE EFFECTIVE

Typically in the U.S., the National Weather Service (a division of NOAA) puts out a network of weather monitoring stations spaced out across the country, and that data gets fed into forward-looking models that help predict the weather. Dr. Doug Cobos, research scientist at METER says, “What people are finding out is that putting in a sparse network of very expensive systems has done really well. It’s been a good thing. But the spatial gaps in those networks are a problem, especially for agriculture producers and ranchers. They need to know what’s happening where they are.”

MESONETS IMPROVE SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION

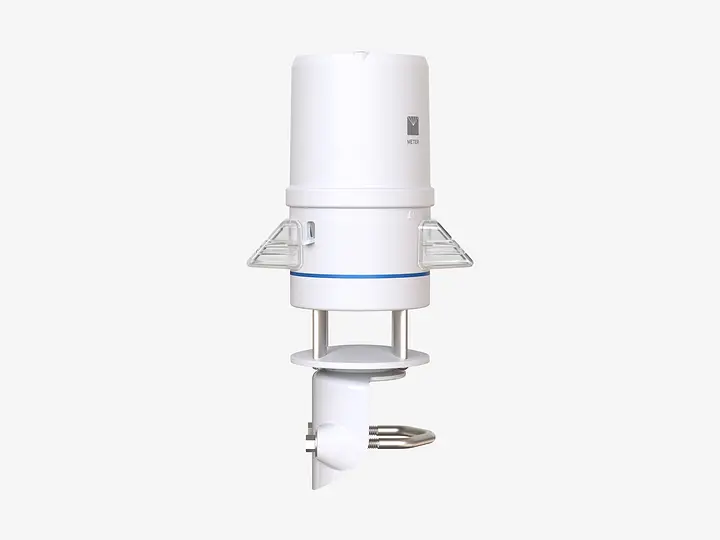

Mesonets present a practical solution for the need to fill in data gaps between large, complex weather stations. The Montana Mesonet currently has 57 stations interspersed throughout the state, and through partnerships with both the public and private sector, they’re adding more stations every year. At each location, the Montana Mesonet team installs METER all-in-one weatherstations, soil moisture sensors, NDVI sensors and data loggers that integrate with ZENTRA Cloud: an easy-to-use web software that seamlessly integrates into third-party applications through an API. Hyde says the system enables better spatial distribution and reliability.

“When we were deciding on equipment we asked ourselves: What kind of technology should we use? It had to provide high data integrity. It had to be easy to deploy and maintain. And it had to be cost effective. There’s not a lot of people in that sector. METER systems are low profile, they’re affordable, and the reliability is there.”

– Kevin Hyde, Montana Mesonet Manager

Forget complicated and costly. If you need an all-in-one weather station or a soil moisture sensor that is incredibly simple to install, low maintenance, and can withstand harsh weather conditions, we've got you covered. METER makes scientific-grade accuracy easy and affordable, so you can discover more—and work less.

Case studies, webinars, and articles you’ll love

Receive the latest content on a regular basis.