Performance is defined by your unique measurement needs. For example, if you’re measuring in a remote location where you can’t access the site routinely, you’ll need extremely robust instrumentation. Robust weather monitoring equipment is also needed if people’s lives are at stake (i.e., if a sensor breaks and a flash flood isn’t detected, people’s lives could be in jeopardy). So in these situations the robustness of a weather monitoring system will drive the relative performance. Other scenarios might be as follows:

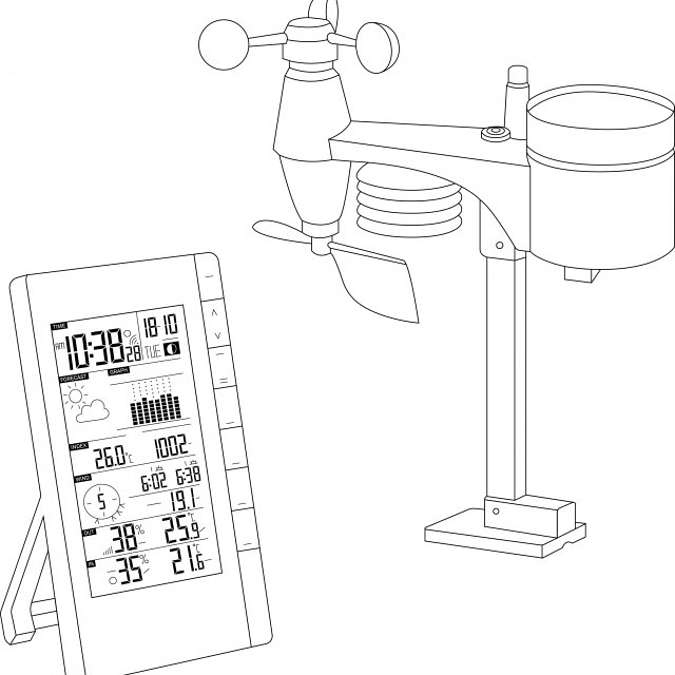

Scenario 1: You may be a climatologist monitoring air temperature to study the effects of climate change. If so, you’ll need a continuous, accurate record of air temperature for several decades. In this case, both the accuracy and the stability of a weather station or weather monitoring solution is the driving factor that affects the performance relative to your measurement needs.

Scenario 2: If you’re running a huge network of remote weather stations, and the cost of making a field trip for maintenance and installation is significant and actually dwarfs the cost of purchasing the equipment in the first place, then possibly the maintenance requirements of the instrument are what drive the performance for your application.

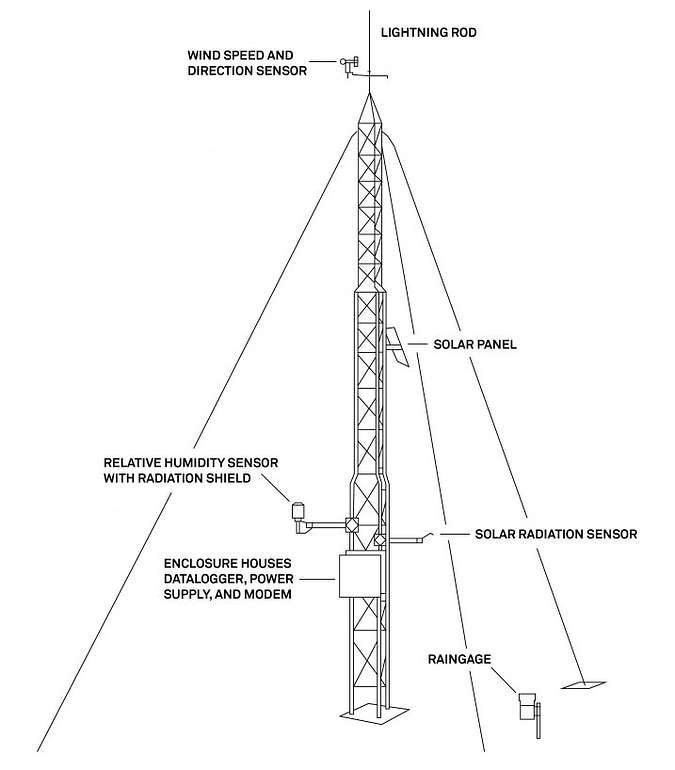

Scenario 3: Researchers often need specialized measurements. You may need more than the typical weather measurements such as air temperature, humidity, and rainfall to answer the research question. In this case, the type of measurement suite containing the specialized measurements you need are what drives the performance of the weather station.

Scenario 4: Some systems have three-season capabilities vs four-season capabilities. Four-season systems are heated and can function and give accurate results in high-latitude wintertime. If you’re studying wintertime precipitation you’ll need a heated rain gauge that can capture the snow precipitation. However if you’re doing an agricultural study, a four-season system won’t be important to you because plants aren’t growing.

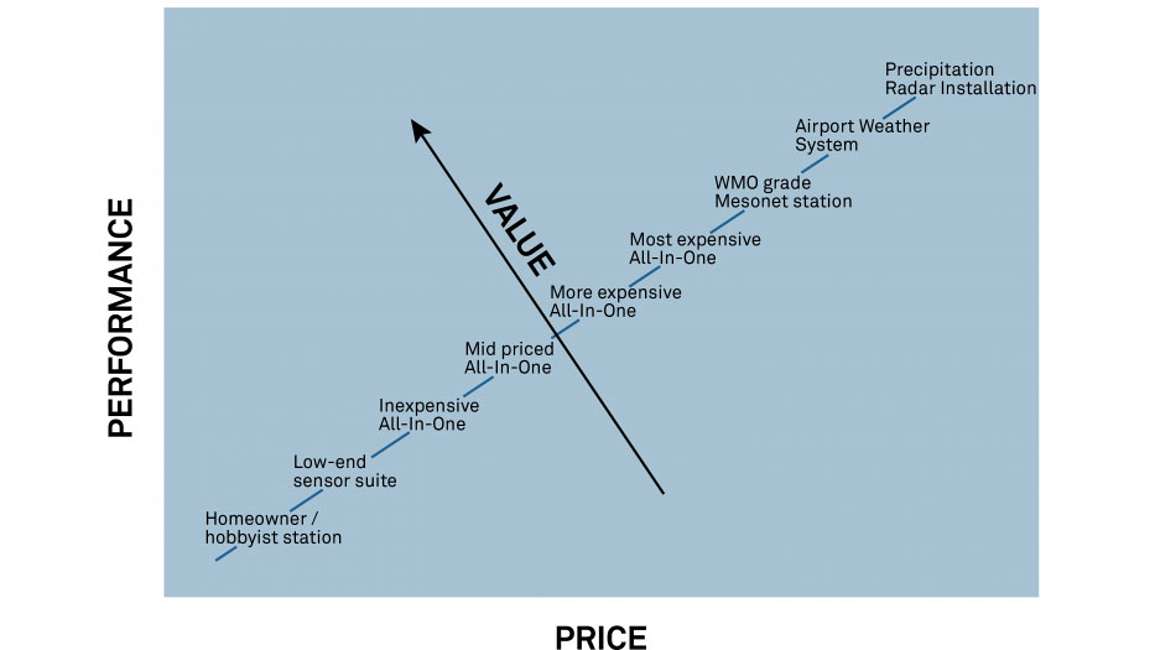

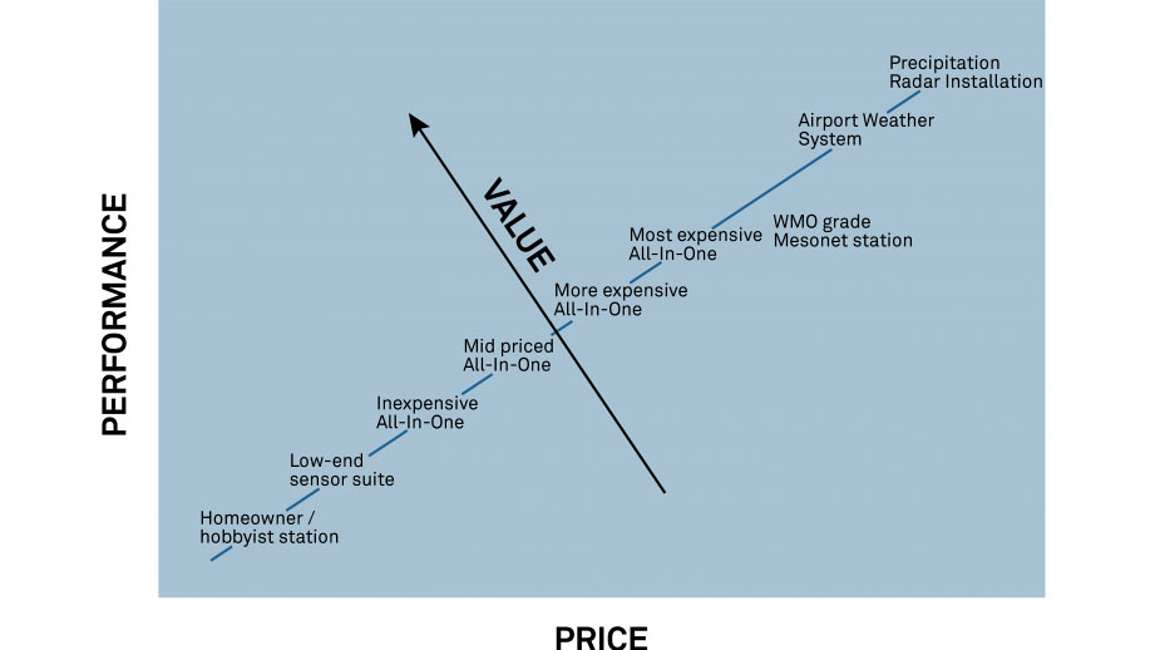

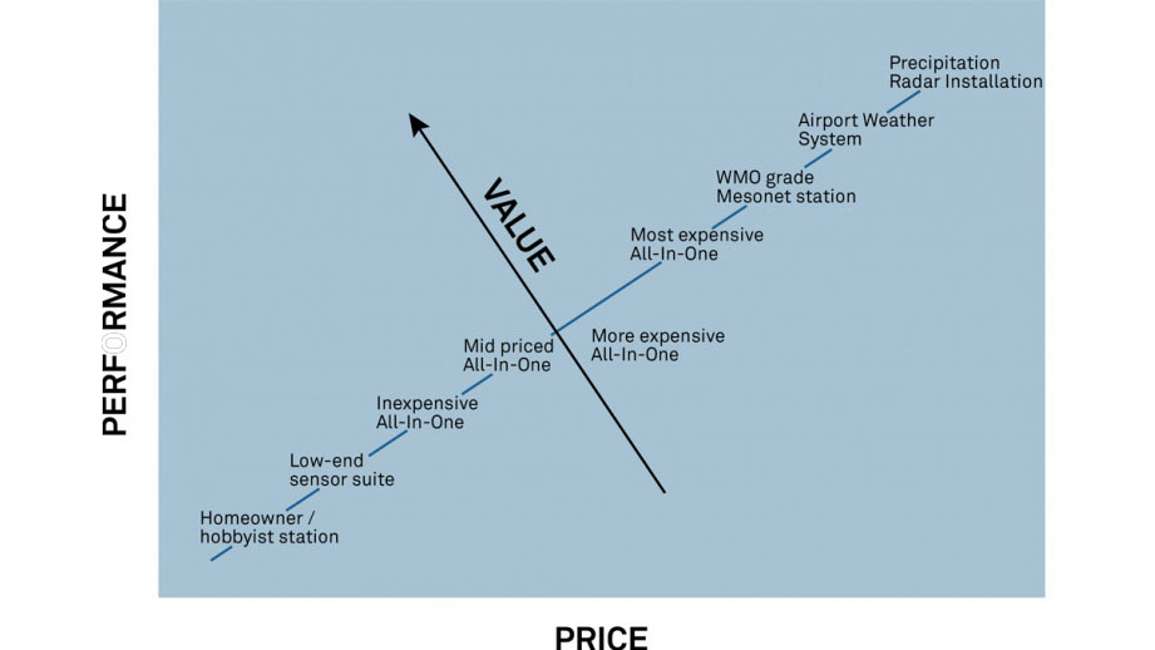

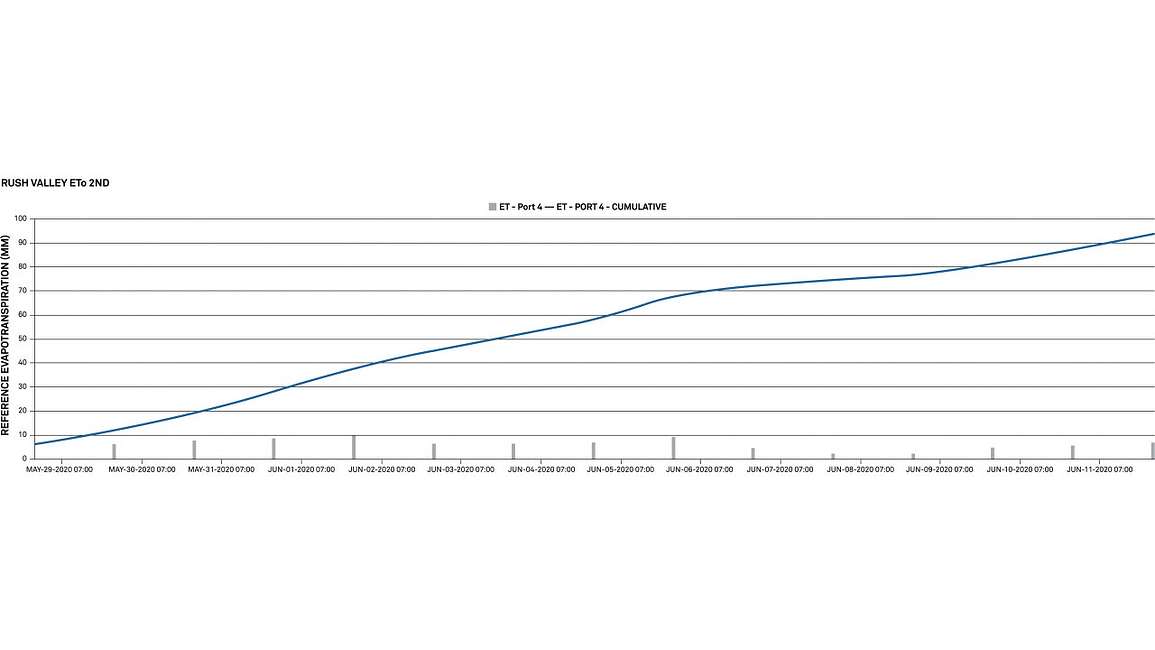

Scenario 5: Power requirements will be important if you’re monitoring at a remote location. You’ll need a battery-powered system with low power requirements, so you can reduce travel time and cost. Thus in a performance vs. value graph, any solutions that don’t meet yourweather monitoring requirements move lower on the value axis, and any that do meet your requirements move higher on the value axis. For example, if a particular WMO-grade system needs so much routine maintenance you can’t scale your network, it may move lower on the value axis, as shown in Figure 3.