Perfecting Turfgrass

A delicate balance

Many athletes don’t like artificial turf. They say it’s hot, uncomfortable to run on, causes burns when you slide or fall on it, and changes the way a ball moves. Professional women’s soccer players even started a lawsuit over FIFA’s decision to use artificial turf in the 2015 Women’s World Cup.

A PERFECT RESEARCH OPPORTUNITY

Some universities—including Brigham Young University—have responded by using natural turf fields for practice and in their stadiums. The challenge is to develop plants and management practices that help the turf stand up to frequent use and allow it to perform well even during the difficult fall months. It’s a perfect research opportunity.

PERFECTING WATER AND NUTRIENTS FOR OPTIMAL PERFORMANCE

BYU turf professor, Dr. Bryan Hopkins, and his colleagues in the Plant and Wildlife Department, have set up a new state-of-the-art facility to study plants and soil in both greenhouse and natural conditions. The facility includes a large section of residential and stadium turfgrass.

BEFORE SOIL SENSORS

Initially, BYU maintained the turf farm grass on a standard, timer-based irrigation control system, but over time they realized that understanding the performance of their turf relative to moisture content and nutrient load is crucial. One year during Memorial Day weekend their turf farm irrigation system stopped working when no one was around to notice. During those four days temperatures rose to 40 °C (100 °F), and the grass in the field slipped into dormancy due to heat stress.

ENVISIONING A FAILPROOF SYSTEM

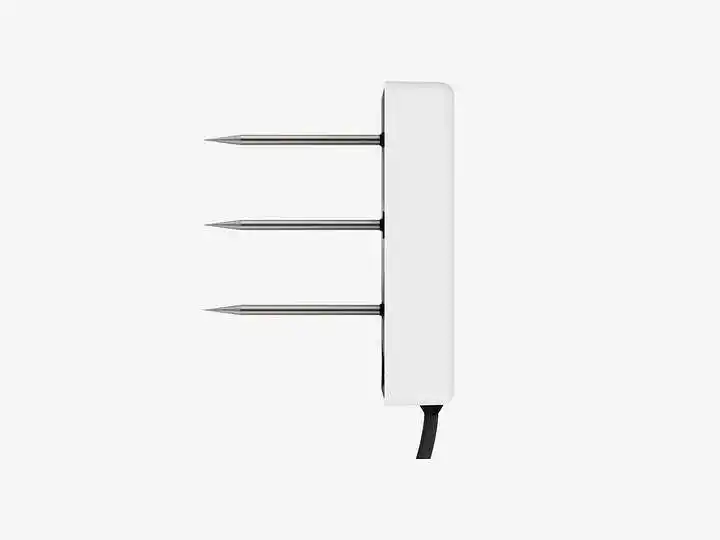

In response, Dr. Hopkins began imagining a system of soil moisture sensors to constantly monitor the performance of the turf grass. He wanted not only to make sure the turf never died but also to really understand the elements of stress so they could do a better job growing healthy turf.

WATER CONTENT + WATER POTENTIAL—BETTER TOGETHER

Soon after, fellow scientists, including Dr. Neil Hansen, installed METER water content and water potential sensors to measure water moving beyond the root zone. Combining these measurements, they could clearly see when the grass was reaching stress conditions and how quickly the turf went from the beginning of stress to permanent wilting point. Ancillary measurements of temperature and electrical conductivity provide an opportunity for modeling surface and root zone temperature as well as fertilizer concentration dynamics.

ERRORS REVEALED

What the researchers learned was that they were using too much water. Dr. Colin Campbell, a METER scientist who worked with BYU on sensor installation, says, “We found in the first year that the plants never got stressed at all. So we allowed the water potential at 6 cm to drop into the stress range while observing WP at 15 cm, reducing irrigation inputs in order to push the roots deeper.”

In turfgrass, drought stress is not the only problem. Overwatering leads to fungus and removal/flushing of the nutrients, which costs money and time to correct. In the video below, Dr. Campbell explains why there is often a fine line between too wet and too dry. Monitoring both water content and water potential keeps turfgrass at optimal moisture levels.

WHAT THE FUTURE HOLDS

The researchers wanted to make sure that if they went down to certain stress levels, they wouldn’t cause harm to the plants, so they installed an ATMOS 41 weather station to monitor evapotranspiration and calculate irrigation application rates. They also began measuring spectral reflectance (METER NDVI/PRI sensor) to monitor changes in leaf area (NDVI) and photosynthesis (PRI). Seeing all this data in ZENTRA Cloud (METER’s data software) will enable them to see the impact on the plants as the turf is drying down.

Click the link below to read the full version of the BYU story with detailed graphs.

Case studies, webinars, and articles you’ll love

Receive the latest content on a regular basis.